Haidar Eid

Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & SocietyVol. 6, No. 1, 2017, pp. 64-78

(CC) 2017 H. Eid – This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0), permitting all non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Post-Oslo Palestine

Today, [Said’s] words on Oslo are the soundingsof a prophet.

—Sandy Tolan(2013)

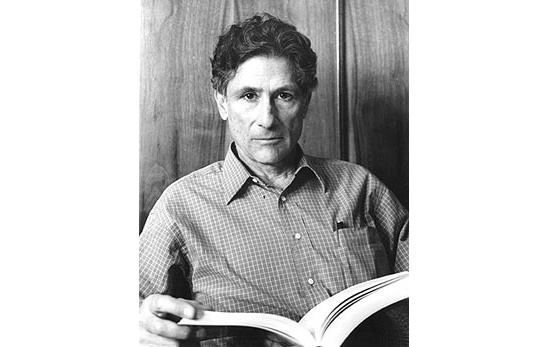

It is to the premise of Edward Said as a figure of dissent that I am inclined to subscribe in the course of this paper. My task in this endeavor is to critically trace some of the ideas conducive to Edward Said being the oppositional intellectual, the agent provocateur, in post-Oslo Palestine. It is what Said (1983) would call a “contrapuntal reading”as a “counter-narrative.” It is a Saidian reading that attempts to understand the Oslo Accords, their disastrous consequences and the power mechanisms that led to them. It is worth noting that Said’s (1999) concern stems from the fact that as an “Oriental” Palestinian who grew up in Egypt, Palestine, and Lebanon—all subject to the domination of the colonizing West—he found it important to define the impact of the United States, where he later received his education and which has had such a profound effect on his own life and that of all other Orientals. As he says in the introduction to the re-edited version of Orientalism (1978/1994), he writes from the perspective of an Arab/Palestinian with a strong concern and empathy for the region (p. 25). This identification is obvious from such statements as this: “Orientalismis written out of an extremely concrete history of personal loss and national disintegration,” recalling Golda Meier’s “notorious and deeply Orientalist comment about there being no Palestinian people,” which had been made only a few years before he wrote the book in the second half of the 1970s (Said, 1978/1994, p. 337).

In a series of articles and books distinguished for their inclusiveness, Said (1980, 1993a, 1993b, 1994, 1995, 1998, 2000) presents a profound and nuanced analysis of the Israeli-Palestinian “conflict,” following Vico’s conviction that human culture, since it is man-made, can be positively shaped by human efforts. Said’s consistent argument has been that what needs to be addressed with regard to the Zionist-Palestinian “conflict” is an alternative representation that is necessarily “secular” in its treatment of the Palestinian and Jewish questions — an alternative that never denies the rights of a people, but rather guarantees total equality and abolishes apartheid, Bantustans, and separation in Palestine. In contrast with the main-stream media’s ahistorical (mis)representation, his argument is a historical one. It is a reading that maintains that any attempt to understand the Oslo Accords, their consequences, and the power mechanisms that had led to them, needs a re-reading of the close relationship between Zionism, American Imperialism, and Arab reactionism.

Much has been said and written about the Oslo Accords. The signatories claim that these much debated documents, in principle, opened up new possibilities for “cooperation” between what has for so long seemed to be irreconcilable positions. Yasser Abed Rabo and Youssi Beilin, the signatories of the 2003 Geneva Initiative, 1 which is an extension of the Oslo Accords, believe that “the only [emphasis added] solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is the establishment of two-states.” And, in what sounds like a warning, the latter adds that the window for a two-state solution will not be available indefinitely and Israel will be forced to deal with the “demographic threat” imposed on it by the Palestinians in historic Palestine. (Beilin, 2013)

The Accord and the Initiative have legitimated apartheid. Both documents include a language that is, euphemistically, reminiscent of the series of laws known collectively as the Group Areas Act (GAA), which forced the relocation of millions of non-white South Africans into racially specific ghettos. It was created to split racial groups up into different residential areas. Like in apartheid South Africa, where the most developed areas were reserved for the white people, and 84% of the available land was granted to the same racial group, who made up only 15% of the total population, in Palestine even the 22% of the historic land on which an “independent state” is supposed to be declared is, according to the Oslo Accords, “disputed.” In the South African case, the 16% remaining land was then occupied by 80% of the population. But, contrary to the Palestinian case, that was never given legitimacy by the leadership of the Indigenous population.

Furthermore, is the establishment of an independent state, as the solution to the Palestinian problem even possible? The argument of the leadership of the Palestinian National Authority (PNA), is that only negotiations 2 can solve the issue. For twenty years, negotiations have not moved the Israeli position at all; the Camp David negotiations reached the impasse predicted by both the Palestinian left and the anti-Zionist Israeli left. Ehud Barak’s 1999 red lines 3 are now very well known, and Benjamin Netanyahu’s platform leads to nothing more than a canton for native Palestinians. Add to this the fact that the establishment of a Palestinian state is not mentioned in any of the clauses of the Oslo Accords, thus leaving the matter to be determined by the balance of power in the region. This balance tilts in favor of Israel, which rejects the establishment of a sovereign Palestinian state, in spite of its recognition of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). No Israeli party, whether left or right, is ready to accept a Palestinian state as the expression of the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination as defined by international law. The Zionist left is prepared to negotiate with the Palestinians in order to give them an advanced form of self-rule that will be called a state, and through which the Palestinians will be enabled to possess certain selected features of “independence,” such as a Palestinian flag, a national anthem, and a police force. Nothing more! This was Barak’s “generous” offer in Camp David in 2000, where Israeli-Palestinian negotiations to reach a final-status deal was brokered by American president Bill Clinton. The right, on the other hand, is not prepared to give the Palestinians even these semblances self-rule. Their vision of the future is rather that the Palestinians should be allowed to run their own affairs under strict and binding Israeli control.

But facts on the ground tell another story. In shocking statistics, Said (1995) shows how the successive governments of Israel had accelerated settlement expansion and land seizure in the occupied West Bank. He concludes, for example, that what the Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak’s “dovish” government was fighting for was the preservation of settlements, the maintenance of control over the Palestinian occupied territories as a part of the “Land of Israel,” and the dominance of Palestinians through other Palestinians. Settlement activity in the West Bank continues, as do the confiscation of land and the opening of zigzag roads to service the settlements. Notably, the number of Jewish settlers has risen from 193,000, when the Oslo Accords were signed, to 600.000. (There are separate “Jews only” roads for settlers and other roads for native Palestinians!) No Israeli government has ever been willing to commit itself to the complete evacuation of settlers from the West Bank. Yet this is a basic pre-condition for the creation of an “independent Palestinian state,” which is impossible in light of Israel’s commitment to the settlers. In order to guarantee the security of the settlements and ensure their future development, Israel is bound to control the greater part of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Furthermore, in any future contingency it is certain that Israel will invoke its security needs to justify tightening its control over the Jordan Valley, thus, again rendering the project of an independent Palestinian state impossible (Said, 2000).

This paper maintains that, based on Edward Said’s (1995, 2000) early reading of the accords, the two-state solution, under present conditions, denies the possibility of real coexistence based on equality. This is because the Oslo Accords accept the Zionist consensus and, for the first time in the history of the conflict, seek to legitimize Israel as a Jewish state in historic Palestine. In these documents, therefore, Israel would appear to have been confirmed as the “state of all the Jews” and never “the state of all of its citizens.” The logic of separation implicit in these documents implies some fundamental contradictions and begs certain serious questions.

Jerusalem has suffered and is still suffering from the continuation of settlement activity, the building and expansion of Jewish neighborhoods, the confiscation of Jerusalem IDs—that is, ethnic cleansing; the policy of “facts on the ground”leaves no room for future Palestinian control over the city.

In addition, Palestinian refugees living outside the West Bank and the Gaza Strip are experiencing increasing difficulties, especially in places like Lebanon and Syria, and are waiting for the day they can return to Palestine and be compensated for their confiscated property. This is a right guaranteed by UN Resolution 194. Meanwhile, the Palestinian community in Israel is prevented from coexisting on an equal footing with Israeli Jews. Israel’s state policy against its Palestinian citizens amounts to apartheid, as defined by the International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid and ratified by United Nations General Assembly Resolution 3068 (XXVIII) of 30 November 1973. 4 Needless to say, the PNA does not represent either of those two large segments of the Palestinian people.

Said’s Peace and Its Discontents (1995) and The End of the “Peace Process” (2000) are about the current situation in post-Oslo Palestine. The questions raised in these collections of articles and essays are of paramount importance. Had Israel, under the Ashkenazi Zionist Labour government, decided to recognize the Palestinian people as a people when it signed the Oslo accords? Are the Oslo accords a radical change in Zionist ideology with regard to “gentile Palestinian non-Jews?” Do the accords guarantee the restoration of a long-lasting, comprehensive peace? And does the current leadership of the PLO represent the political and national aspirations of the Palestinian people? These are the kinds of questions Said tries to answer. He sums up these answers in what seems to be the gist of his latest books and articles about the Oslo accords: “No negotiations are better than endless concessions that simply prolong the Israeli occupation. Israel is certainly pleased that it can take the credit for having made peace, and at the same time continue the occupation with Palestinian consent” (Said, 2000, p. 25). Oslo, therefore, has created what Said (1995) called “a kingdom of illusions.”

When The End of the “Peace Process”was written, the Israeli prime minister at the time, Ehud Barak,supported the idea of the establishment of a demilitarized Palestinian state, or rather a Bantustan in most of the Gaza Strip and parts of the West Bank. Said holds that the program of Barak’s One Israel government did not challenge the status quo at the time, nor did it allow the Palestinian people to exercise the minimum of their national and political rights. Barak’s clear platform during the elections, which he confirmed in his first victory speech, included his “red line concessions”: no return to the borders of 4th of June, 1967; no dismantling of the Jewish settlements in the Gaza strip and the West Bank; no return of Palestinian refugees; no backing down on Jerusalem as “the undivided, eternal capital city of Israel”; and no unilateral declaration of an independent sovereign Palestinian state that can have a military on the western bank of the Jordan River. These reservations remain to be the platform of all Israeli governments, right and left, until today.

The so-called safe passage that was established between Gaza and the West Bank is not free of “interference from Israeli authorities,” as mentioned in the Oslo Accords. Israel issues magnetic cards—similar to South African passes—which are required by Palestinians to travel on this passage. Further, Israel reserves the right to arrest any Palestinian “suspect”on this route. Thus, the opening of the “safe passage” did not change the enforced divisions between the Gaza Strip and the West Bank—divisions which have been enforced by Israel since 1991, and solidified since 2007. This fate was predicted by Said in 1995 with the publication of his prophetic critique of the mentioned accords, Peace and Its Discontents.

Hence, the Palestinian state that Israel accepted is a Bantustan, a canton, a demilitarized state that lacks the necessary components of a sovereign, independent state—that is, a state that has a dependent economy, that lacks unified territory, and has no military power. The real reality is that the Israelis put the Palestinians on confined and controlled reservations, carefully and intensely restricting them even from being able to visit the great bulk of what, just a few years before, was their country. According to Said (1994), this is a state that will be accepted by the official leadership of the PLO who, by signing the Oslo Accords, completely surrendered to Israel (p.95).

The Oslo Accord was claimed to be the first step towards self-determination and an independent state. But it is clear now, twenty years after the famous ceremony at the White House, that no independent, sovereign state will be established in the short run, because Oslo simply ignored the existence of the Palestinian people as a people. And if any Palestinian intellectual speaks out about this great injustice, s/he is automatically accused of terrorism and incitement. Hence the banning of Said’s Peace and its Discontents in the Palestinian occupied territories.

Said (1993b, 1995) argues consistently and convincingly that the Oslo Accords do not guarantee the establishment of a sovereign, independent state. Further, they do not guarantee the return of the refugees; the demolishment of all Jewish settlements; compensation for those who lost, and are still losing, their homes, lands and properties; the release of all political prisoners; the opening of all checkpoints; or the holding of free elections after the withdrawal of all Israeli troops from the territories that have been under occupation since 1967.

The Gaza Strip, however, is seen by the Palestinian Authority (PA) as one of three building blocks of an independent state, although it is geographically separated from the second block, the West Bank. The third block, Jerusalem, is under total Israeli control. Like Edward Said, none of the Palestinians in the occupied territories believe that the different “semi-autonomous” zones in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank — that is, the ones that fall under category A—can lay the foundation for an independent state even if the boundaries of such a state are declared unilaterally.

Palestine de-Osloized

Said (1994, 1995) compares the current situation in Palestine with apartheid South Africa. The tribal chiefs of the South African Bantustans used to believe that they were heads of independent states. The African National Congress, despite its many compromises with the National Party, never accepted the idea of separation and Bantustans. Said maintains that at the end of the millennium the Palestinian leadership, on the other hand, boasted of having laid the foundation for a Bantustan, claiming it to be an independent state. This is undoubtedly the ultimate thing Zionism can offer to its oriental “Other” (see Orientalism, 1978/1994) after having denied her/his existence for a century, even after that same Other has proved that s/he is human. For Zionism’s continued presence in Palestine, the Other must therefore be assimilated and enslaved without being conscious of her/his enslavement. Hence, the granting of semi-autonomous rule over the most crowded Palestinian cities, and the logic behind Oslo.

From a Saidian dialectical perspective, The Oslo Accords, however, never saw the antithesis Israel has created as a result of displacement, exploitation, and oppression; it also has failed to see the revolutionary consciousness that has been formulated throughout the different phases of the Palestinian struggle. Nor does it take into account the legacy of civil and political resistance that has become a trademark of the Palestinian struggle. The formation of the Boycott National Committee—in 2007, two years after the BDS call 5 made by more than 170 Palestinian civil-society organizations, and which now enjoys an overwhelming consensus—the attempts to break the siege imposed on Gaza, the resistance to Israel’s war machine in 2009 and 2012, and the tearing down of the wall separating Gaza from Egypt, all represent the beginning of what I call the de-Osloizing of the Palestinian mind (Eid, 2009). Most events that have taken place in Gaza since the 2006 elections represent an outright rejection of the Oslo Accords and their consequences. And when we bear in mind that 75–80% of Gazans are refugees, the results of 2006 elections in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, in which an anti-Oslo organization won, become more comprehensible in its anti-colonial and anti-Oslo context.

Palestinian deterrence depends on the fact that they have what Said calls, “the higher moral ground” (2001), and their victory at the end will be the inevitable result of their sumud (steadfastness) that has not wavered despite the feeling that they have been left on their own (Said, 1993a).

As Said (1993b) argues very eloquently in his initial reaction to the (in)famous handshake on the While House lawn, the possibility of peace with justice at this moment is far from realization. The impossibility of the realization of the national dream of one third of the Palestinian people—that is, those who live in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank—has brought forward the embarrassing question of the rights of the remaining two thirds, namely the dispossessed refugees living in miserable camps.

What is the Palestinian cause if not the right of return of the refugees both inside and outside Palestine? Is there a slight possibility of having peace in the Middle East without resolving this question? If, as some Israeli leaders claim, there is a way of finding a “just solution” that does not include their return, does that guarantee a just comprehensive peace? The whites of apartheid South Africa defined the institutions of the country as democratic—albeit a white democracy, by and for whites only. Native Africans never recognized the “white nature”of that country. The idea of defining the country as exclusively white and democratic at the same time was never accepted by the international community. It was considered blatant racism.

That is precisely what the call for the recognition of Israel as a “pure” Jewish state means. Forget the 6 million refugees scattered all over the world as a result of the process of “ethnic cleansing” that accompanied the establishment of Israel in 1948 (see Pappe, 2008). According to this formula, informed by the Oslo Accords, the Palestinians are only those who live in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. “The Middle East conflict” will be resolved if the latter are given a flag and three to four truncated Bantustans with a chief whom we can call a president.

The bid for Palestinian statehood

How would Edward Said have reacted to the Palestinian bid at the United Nations for statehood? Certainly, he would have condemned the “induced euphoria” that characterizes discussions within the mainstream media around the declaration of an independent Palestinian state, which ignores the stark realities on the ground. Depicting such a declaration as a “breakthrough,” and a “challenge” to the defunct “peace process” and the right-wing government of Israel serves to obscure Israel’s continued denial of Palestinian rights while reinforcing the international community’s implicit endorsement of an apartheid state in the Middle East.

The drive for recognition is led by Mahmoud Abbas, the Chairman of the Ramallah-based Palestinian Authority. It is based on the decision made during the 1970s by the Palestine Liberation Organization to adopt the more flexible program of a “two-state solution.” This program maintains that the Palestinian question, the essence of the Arab-Israeli conflict, can be resolved with the establishment of an “independent state” in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, with East Jerusalem as its capital. In this program, Palestinian refugees would return to the state of “Palestine” but not to their homes in Israel, which defines itself as “the state of Jews.” 6 Yet “independence” does not deal with this issue, neither does it heed calls made by the 1.2 million Palestinian citizens of Israel to transform the struggle into an anti-apartheid movement since they are treated as third-class citizens.

All this is supposed to be implemented after the withdrawal of Israeli forces from the West Bank and Gaza. Or will it merely be a redeployment of forces as witnessed during the Oslo period? Proponents of this strategy claim that independence guarantees that Israel will deal with the Palestinians of Gaza and the West Bank as one people, and that the Palestinian question can be resolved according to international law, thus satisfying the minimum political and national rights of the Palestinian people. Forget about the fact that Israel has as many as 573 permanent barriers and checkpoints around the occupied West Bank, as well as an additional 69 “flying” checkpoints; you may also want to ignore the fact that the existing “Jewish-only” colonies have annexed more than 54 percent of the West Bank.

This same idea of “independence” was once rejected by the PLO because it did not address the “minimum legitimate rights” of Palestinians and because it is the antithesis of the Palestinian struggle for liberation. What is proposed in place of these rights is a state in name only. In other words, the Palestinians must accept full autonomy on a fraction of their land, and never think of sovereignty or control of borders, water reserves, and most importantly, the return of the refugees. That was the Oslo agreement and it is also the “Declaration of Independence.”

Further, this declaration does not promise to be in accordance with the 1947 UN partition plan, 7 which granted the Palestinians only 47 percent of historic Palestine, even though they comprised over two-thirds of the population. Once declared, the future “independent” Palestinian state will occupy less than 20 percent of historic Palestine. By creating a Bantustan and calling it a “viable state,” Israel will get rid of the burden of 3.5 million Palestinians. The PA will rule over the maximum number of Palestinians on the minimum number of fragments of land—fragments that Palestinians can call “The State of Palestine.” Unlike South Africa’s infamous Bantusans, this “state” has already been recognized by tens of countries. 8

The much-talked about and celebrated “independence” will simply reinforce the same role that the PA has played under Oslo — namely, providing policing and security measures designed to disarm the Palestinian resistance groups. These were the first demands made of the Palestinians at Oslo in 1993, Camp David in 2000, Annapolis in 2007,and Washington in 2011.

Meanwhile, within this framework of negotiations and demands, no commitments or obligations are imposed on Israel.

Just as the Oslo Accords signified the end of popular non-violent resistance of the first intifada, this declaration of independence has a similar goal, namely ending the growing international support for the Palestinian cause since Israel’s 2008–2009 winter onslaught on Gaza and its attack on the Freedom Flotilla in May 2010. Yet the declaration falls short of providing Palestinians with even minimal protection and security from any future Israeli attacks and atrocities. The invasion and siege of Gaza was a product of Oslo; before the Oslo Accords were signed, Israel never used its full arsenal of F-16s, phosphorous bombs, and DIME weapons to attack refugee camps in the Gaza and the West Bank. Over 1,200 Palestinians were killed from 1987–1993 during the first intifada. Israel eclipsed that number during its three-week invasion (22 days) in 2009; it managed to brutally kill more than 1,443 in Gaza alone. This does not include the victims of Israel’s siege, in place since 2006, which has been marked by closures and repeated Israeli attacks both before the invasion of Gaza and since.

As Saree Makdisi (2012) puts it,

in the wake of Mahmoud Abbas’s UN General Assembly speech . . . it was clear to many Palestinians that the statehood bid was not really intended to address or secure the rights of all Palestinians, but rather to. . . tactically reframe rather than strategically transform the pointless negotiations game that he and his associates have been playing for two decades now. (pp. 91–92)

Ultimately, what this “declaration of independence” offers the Palestinian people is a mirage, an “independent homeland” that is a Bantustan-in-disguise. Although it is recognized by so many friendly countries, it stops short of providing Palestinians freedom and liberation. Critical debate—as opposed to one that is biased, demagogic—requires scrutiny of the distortions of history through ideological misrepresentations. What needs to be addressed is a historical human vision of the Palestinian and Jewish questions, a vision that guarantees complete equality, and abolishes apartheid, instead of recognizing a new Bantustan 17 years after the fall of apartheid in South Africa.

Said’s vision: One state for all (liberation as opposed to independence)

What I have tried to do is to show that the Palestinian experience is an important and concrete part of history, a part that has largely been ignored both by the Zionists who wished it had never been there, and by the Europeans and Americans who have not really known what to do with it. I have tried to show that the Muslim and Christian Palestinians, who lived in Palestine for hundreds of years until they were driven out in 1948, were unhappy victims of the same movement whose whole aim had been to end the victimization of Jews by Christian Europe. Yet it is precisely because Zionism was so admirably successful in bringing Jews to Palestine and constructing a nation for them, that the world has not been concerned with what the enterprise meant in loss, dispersion, and catastrophe for the Palestinian natives.

—Edward W. Said (1980), The Question of Palestine, p. xxxix

In order to understand all the events that have been taking place in post-Oslo Palestine, including the wars on Gaza in 2009, 2012, and 2014, one ought to trace their origin back to 1948. Of importance within this context is the reminder that two thirds of the Palestinians of Gaza are refugees who were ejected from their cities, towns, and villages in 1948. In After the Last Sky (1993a), Said argues that every Palestinian knows perfectly well that what has happened to us over the last six decades is “a direct consequence of Israel’s destruction of our society in 1948” (p. 5). The problem, he argues, is that a clear, direct line from our misfortunes in 1948 to our misfortunes in the present cannot be drawn, thanks to “the complexity of our experience” (p. 5). There is an urgent need, therefore, to counter the Nakba in order to achieve peace with justice.

Nonetheless, Said is not against a political solution in principle. On the contrary, he holds that a minimum fair solution at this stage must be based on resolutions of international legitimacy that accord the Palestinian people some of their rights — that is, self-determination, establishment of an independent state, return of dispossessed refugees and Jerusalem, and the removal of the Jewish settlements. However, ironically, what the Oslo Accords have led to is a situation that was not envisaged by its signatories: the extreme difficulty — not to say impossibility — of establishing a sovereign, independent Palestinian state on 22% of historic Palestine. Hence his defense of the establishment of a secular democratic state in Palestine-Israel in which all citizens are treated equally regardless of their religion, sex, and color (Said, 1998, 2001). A comprehensive peace, for him, means that Israel — which dispossessed 800,000 Palestinians in 1948, occupied the West Bank, Gaza, Golan, and Sinai in 1967, annexed Jerusalem and Golan, invaded Lebanon in 1982, expropriated Palestinian land, built settlements, killed more than 2,000 Palestinians during the intifada (1987–1993), uprooted trees, assassinated Palestinian leaders, banned books, demolished houses, closed universities — should acknowledge the right of Palestinians to exist as a people, their right to self-determination. What Said found “astonishing” is how far, after more than 60 years, supporters of Israel will go to suppress the fact that these years have gone by without Israel restitution, recognition, or even acknowledgment of Palestinian human rights and without connecting that suspension of rights to Israeli official policies.

As mentioned earlier, there is no Israeli nationality while Israel continues to define its national character as Jewish and not Israeli, which effectively excludes all Palestinians and “non-Jews” living in Israel. This, as noted by the United Nations Committee on Social, Economic, and Cultural Rights, “encourages discrimination and accords second class status to [Israel’s] non-Jewish citizens.” 9

Defending a two-state solution is, therefore, an insult to the memory of those who fought for equality and justice — not only in Palestine but also in the American South and South Africa. Thus, Said (2001) comes to the inevitable conclusion that a sovereign, independent Palestinian state is, for the reasons mentioned above, unattainable. The question, therefore, is whether there is an alternative solution. One alternative increasingly to be found in Said’s writings and pronouncements is the idea of a secular-democratic state in Mandatory Palestine in which all citizens are treated equally regardless of their religion, race, or sex. (Said, 1998, 2000) So, how would a decolonized Palestine look without Oslo?

One answer would be that a secular, democratic state is one inhabited by its citizens and governed on the basis of equality and parity, both between the individuals as citizens and between groups which have cultural identities. Inherent in such an arrangement is the condition that the groups living there are enabled to coexist and to develop on an equal footing.

This system is proposed here as a long-term solution that will need much nurturing following the political demise of the project of an “independent Palestinian state” as a result of the Oslo Accords, the siege of the Gaza Strip, and the occupation of the West Bank. The establishment of four Bantustans in South Africa was considered by the international community to constitute a racist solution that could not and should not be entertained. In order to bring that inhumane solution to an end, the apartheid regime was boycotted academically, culturally, diplomatically, and economically until it succumbed and crumbled into pieces. Nothing remains of the old, ethnically cleansed South Africa or the impoverished Bantustans it had created: not the red carpets, the national anthems, or the security apparatuses. This is what racist solutions come to: a corner in the dustbin of history—a museum for the gaze of new generations.

A serious, comprehensive solution to the Palestinian question will not, therefore, neglect the 1948 Palestinians and those who were expelled and dispossessed of their lands on 1948 — namely, the refugees living in miserable camps. The mechanism by which such serious issues can be resolved is not a Bantustanization, a la apartheid South Africa, as suggested by the signatories of the Oslo Accords. Rather, a secular, democratic state where all citizens are treated equally regardless of their religion, sex or color is the right solution that brings an end to the conflict. This is what Edward Said’s political vision is about; it’s a vision that has been taken up by some Palestinian and Israeli activists. (Abunimah, 2006; Atwan, 2008; Barghouti, 2012; Karmi, 2007; Kovel, 2007; Makdisi, 2008; Pappe, 2008; Qumsiyeh, 2004)

Israel, as it has existed for 60 years, is an apartheid state, built on the principles of colonialism, ethnic cleansing, and institutionalized discrimination. A precondition for a decolonized, post-Oslo Palestine would be to dismantle this system and replace it with a democracy for all the people who live there. It should be absolutely clear that, much like what the anti-apartheid activist Seteve Biko argued in the 1970s when asked about the fate of white Afrikaners in post-Apartheid South Africa, the target is not the Israeli Jewish people; it is the racist state and the ruling Zionist establishment. The Israeli Jewish people have a right to live in peace and security, fully protected as citizens in a non-sectarian state. It is just as important that along with pressure, mainly in the form of BDS, there be a clear vision of the future, a vision that will let Israeli Jews understand that they will be stripped of their “legal” privileges, and there will be restitution, but they will have a safe place in a decolonized Palestine with full guarantees for their civil, political, and cultural rights. It has to be a principled and credible vision. Undoubtedly, this vision needs to be developed among Palestinians, but they can benefit from the experiences that South Africans and Irish have had. That is what Omar Barghouti (2012) calls “ethical decolonization.”

Noticeably, polls show that in the West Bank and Gaza, support for the two-state solution has deteriorated, whereas support for a one-state solution has increased. It is also remarkable how low support for a two-state solution has been, given how heavily marketed it is. Among Palestinian refugees who live outside Palestine, support for a two-state solution has always been low — exact figures exist, though. But the reason for this is clear: A two-state solution means that the right of Palestinian refugees to return to most of Palestine will have to be given up. This is why the PLO official leadership gradually excluded Palestinian refugees from decision-making. Finally, among Palestinians inside the 1948 borders of Israel, there is massive support for a state of all its citizens.

Edward Said, the political activist, is what the official Palestinian leadership is not: charismatic, with a political vision and a clear-cut ideological program. Whereas the Palestinian leadership is prepared to recognize a Jewish state alongside a Palestinian state — regardless of what this means, including the discriminatory practices applied by Israel against its non-Jewish, mainly Palestinian citizens and residents since 1948 — Said’s alternative (1998, 2001) makes the necessary link between all Palestinian struggles against the occupation of Gaza and the West Bank and against Israel’s ethnically-based displacement, dispossession, discrimination, and rights violations of more than one million Palestinian citizens; these citizens include some 250,000 internally displaced persons, as well as the 1948 externally displaced refugees, who are entitled to return, restitution,and Israeli citizenship under international law. The Palestinians, for Said, are one people with one cause; to achieve a just peace, the rights of all Palestinians must be addressed. So if — as Saree Makdisi (2012) maintains in his argument regarding the necessity for a one-state solution — Palestinians declare that all they want is a state in the West Bank and Gaza, then that relieves Israel of the challenges of democratic and equal rights for all citizens, including returned refugees.

Palestinian activists in Post-Oslo Palestine, inspired by the legacy of Edward Said, call for an alternative paradigm that divorces itself from the fiction of the two-state/two-prison solution — a paradigm that takes the sacrifices of the people of Gaza as a turning point in the struggle for liberation and builds on the growing global anti apartheid movement that has been given impetus by the events of Gaza in 2009 and 2012, and by the flotilla massacre. De-Osloizing Palestine, for most Palestinian activists, has become a precondition for the creation of peace with justice.

Conclusion

For Said, coexistence in Palestine-Israel is unachievable at the present moment because Israel is not the state of all its citizens, but rather the state of Jews entitled to the “entire land of Israel,” and because no serious attempt has been made by the Israeli side to acknowledge the right of the Other to exist as an equal partner. How are Palestinians — whose entire territory was occupied and society destroyed, who now live under untenable conditions, and whose leadership has acknowledged Israel’s right to exist — supposed to deal with the American-Israeli understanding of “comprehensive peace?” How are they supposed to coexist with a state that still has not declared its boundaries?

To put it differently, has there been any change in the colonialist and exclusivist behavior of Israel, as a settler colony, that indicates that it is somehow prepared to (co)exist in the midst of the Arab world? These are the kinds of questions that Said (2001) thinks need to be addressed, instead of blaming the victims for the mere fact of being victims. At the core of comprehensive peace is justice, non-discrimination, and equality—qualities that Israel denies all Palestinians.

In post-Oslo Palestine, Said remains the controversial “amateur” — a public intellectual who speaks truth to power. As he puts it in his discussion of the role of resistance,“ [it] only takes a few bold spirits to speak out and start challenging a status quo that gets worse and more dissembling each day” (Said, 2000, p. 26). Interestingly his work has consistently striven “to cross rather than to maintain barriers.” (Said, 1994, p.336). His writings on Palestine, in particular, and on the postcolonial world, in general, are a Gramscian manifestation of the pessimism of intellect and the optimism of the will.

References

- Abunimah, A. (2006). One country: A bold proposal to end the Israeli-Palestinian impasse. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books.

- Atwan, A. (2008). A country of words. London, UK: SaqiBooks.

- Barghouti, O. (2012). A secular democratic state in historic Palestine:Self determination through ethical decolonisation.In A.Lowenstein & A.Moore(Eds.), After Zionism: One state for Israel and Palestine(pp. 194–209). London, UK: Saqi Books.

- Beilin, Y.(2010).Interview byA. Zelman.Retrieved from http://arielzellman.wordpress.com/2010/08/19/interview-with-yossi-beilin/

- Eid, H. (2009, March12). De-Osloizing the Palestinian mind. ZNET. Retrieved from https://zcomm.org/znetarticle/gaza-2009-de-osloizing-the-palestinian-mind-by-dr-haidar-eid/

- Karmi, G. (2007). Married to another man. London, UK: Pluto Press.

- Kovel, J. (2007). Overcoming Zionism: Creating a single democratic state in Israel/Palestine. London, UK: Pluto Press.

- Makdisi, S. (2008). Palestine inside out. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

- Makdisi, S.(2012). The power of narrative: Reimagining the Palestinian struggle.In A.Lowenstein & A.Moore (Eds.), After Zionism: One state for Israel and Palestine(pp. 90–100).London, UK: Saqi Books.

- Pappe, I. (2007). The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. Oxford, UK: Oneworld.

- Qumsiyeh, M. (2004). Sharing the land of Canaan. London, UK: Pluto Press.

- Said, E. (1978/1994).Orientalism. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

- Said, E. (1980). The question of Palestine. London, UK: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Said, E. (1983). The world, the text and the critic. London, UK: VintageBooks.

- Said, E. (1988/2001).Introduction. In E. Said and C.Hitchens (Eds.), Blaming the victims(pp. 1–19). London: VintageBooks.

- Said, E. (1993a). After the last sky. London, UK: VintageBooks.

- Said, E. (1993b, October21). The morning after. London Review of Books,15(20). Retrieved fromhttp://www.lrb.co.uk/v15/n20/edward-said/the-morning-after

- Said, E. (1994). The politics of dispossession. London, UK: VintageBooks.

- Said, E. (1995). Peace and its discontents. London, UK: Vintage Books.

- Said, E. (1998, January 10).The one-state solution. The New York TimesMagazine. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1999/01/10/magazine/the-one-state-solution.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm

- Said, E. (1999). Out of place. New York, NY: VintageBooks.

- Said, E. (2000). The end of the “peace process”: Oslo and after. New York, NY:Pantheon Books.

- Said, E. (2001, March1–7). The only alternative. Al-Ahram Weekly, 523.Retrieved fromhttp://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2001/523/op2.htm

- Tolan, S. (2013, September 26). Edward Said and his quest for a just peace. Al-Jazeera. Retrieved from http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2013/09/edward-said-his-quest-for-a-just-peace-201392681712880834.html

Footnotes

- The full text of The Geneva Accord: A Model Israeli-Palestinian Peace Agreement can be found on http://www.geneva-accord.org/mainmenu/english

- See “Abbas calls for peace conference in Moscow amid Putin visit.” Maan News Agency. http://www.maannews.net/eng/ViewDetails.aspx?ID=498864

- See “Israel at the Polls 1999, Introduction. “Elections 1999—Character, Political Culture, and Centrism.”Jerusalem Centre for Public Affairs. http://jcpa.org/dje/articles3/elect99.htm

- See “International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid.” Un General Assembly at http://www.refworld.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/rwmain?docid=3ae6b3c00

- See, Palestinian Civil Society Calls for Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions against Israel http://www.bdsmovement.net/call

- The distinction between “nationality” and “citizenship” in Israel confers on Jews who are not Israeli citizens greater rights and privileges in Israel than those conferred on Israeli “citizens” who lack Jewish “nationality.” This is a distinction unique in today’s world, and not one normally associated with the word “democracy.” (See https://wespac.org/2013/10/08/israeli-court-rejects-israeli-nationality/)

- See the map of Palestine according to the Partition Plan on http://domino.un.org/unispal.nsf/0/3cbe4ee1ef30169085256b98006f540d?OpenDocument

- As of September 27, 2013, 133 (68.9%) of the 193 member states of the United Nations have recognized the State of Palestine. (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_recognition_of_the_State_of_Palestine

- (qtd.in BADIL Occasional Bulletin No. 9 (October 2001) “A Two-State Solution and Palestinian Refugee Rights -Clarifying Principles http://www.badil.org/en/press-releases/54-press-releases-2001/265-press209-01